Souzou: Outsider Art from Japan at the Wellcome Collection

According to a Japanese proverb, “the most beautiful flowers often bloom in hidden places.”

The term ‘outsider art’ was introduced by art critic Roger Cardinal in 1972 to describe ‘art brut’ (the French term for ‘raw’ or ‘rough art’), used by French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the boundaries of the established art scene, and particularly by residents of lunatic asylums and children. The English version of outsider art has been applied to a broader range of artists – including self-taught and naïve art practitioners who were never institutionalized. The art movement is now internationally recognized, in fact an annual Outsider Art Fair has taken place in New York since 1993.

Wellcome Collection’s latest exhibition, Souzou: Outsider Art from Japan (until 30th June), brings together more than 300 works for the first major display of Japanese Outsider Art in the UK, featuring 46 artists – all residents or attendees of social welfare institutions in Japan. ‘Souzou’ has no direct translation in English, but can be written in two ways in Japanese and means either ‘creation’ or ‘imagination.’ The show is curated by Shamita Sharmacharja and organized in association with Het Dolhuys of the Netherlands based Museum of Psychiatry and Tokyo’s Social Welfare Organisation, Aiseikai.

The main emphasis of Japanese institutions was previously very much the work ethic – it was hoped that training people in workshops would improve their chances of finding employment once they left the institution. But the model for social welfare institutions in Japan began to focus increasingly on the non-interventionist teaching of artist Kazuo Yagi, who insisted upon his students’ right to self-expression, regardless of formal training. Today, the not-for-profit organization Haretari Kumottari maintains an audit of all the artists creating work in welfare institutions in order to protect their rights and conserve their artworks.

Hans Looijen, Director of the Het Dolhuys Museum says, “In this remarkable collection you will meet various artists and see their extraordinary works of art. The subject of their thoughts, feelings, and sometimes even obsessions, seem to concern different themes. Some express their deepest desires, lively fantasies, or unload their fondest or suppressed memories. Others are clearly fascinated with ordering the world through a kind of personal system. They all have one thing in common: the artists all communicate to the outside world through their artworks.”

The exhibition explores several key areas. Firstly, how visual expression can offer a release from the confines of ‘language’. Secondly, the process of ‘making’. Outsider art is characterized by the use of unconventional material in repetitive time-consuming processes that can have calming and therapeutic effects.

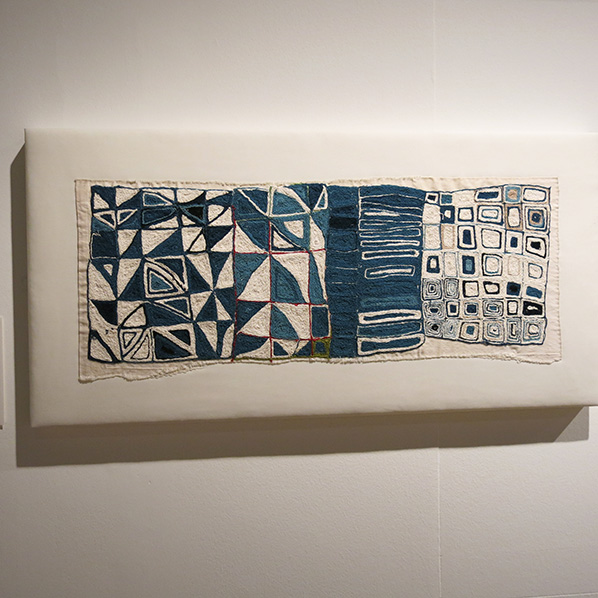

Textile artists Yumiko Kawai and Noriko Tanaka use cloth and thread for their freehand stitching. Satoshi Morita’s tapestries are assembled entirely from the leftover threads of other people’s discarded sewing or embroidery, which he keeps packed in a cardboard box.

Shota Katsube styles action figures out of Arutai (twist-ties) that are conventionally used to fasten bin liners. He finishes one doll in 5-6 minutes and each doll (a unique, self-designed anime soldier) stands at about 3 cm tall.

In a section on ‘representation’ hairdryers, windows and baseball gloves are elevated to objects of beauty. This part of the exhibition explores how the daily life of the artists is interpreted through their subjective artworks. MK takes images from adverts and magazines and presents them in his own unique way. Meantime, Marie Suzuki’s canvases burst with breasts and genitalia, human figures that are neither adults nor children… and innumerable scissors. The dubiousness of the idea that human life comes from the womb, disgust towards female and male genitalia and, conversely an obsession with these things inspires her. Drawing also helps her to relax.

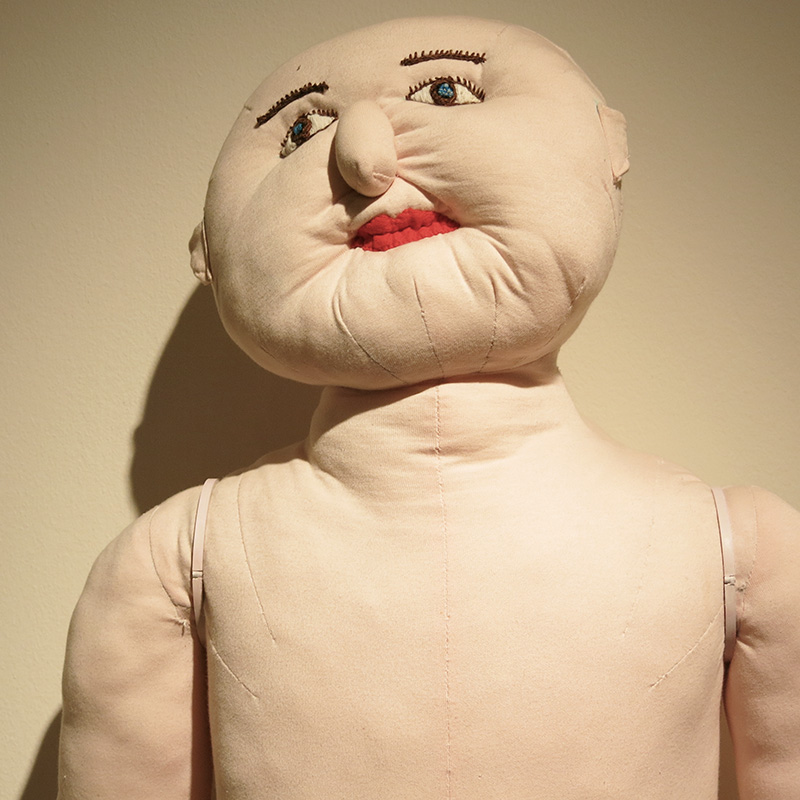

The part of the exhibition devoted to ‘relationships’ examines the ways in which the artists depict themselves and their involvement with others. Sakiko Kono’s life-size dolls represent the staff and friends who have been kind to her in the Azami residential facility that has been her home for the past 55 years. Yoko Kubota’s drawings are inspired by the images of models in fashion magazines that she aspires to be.

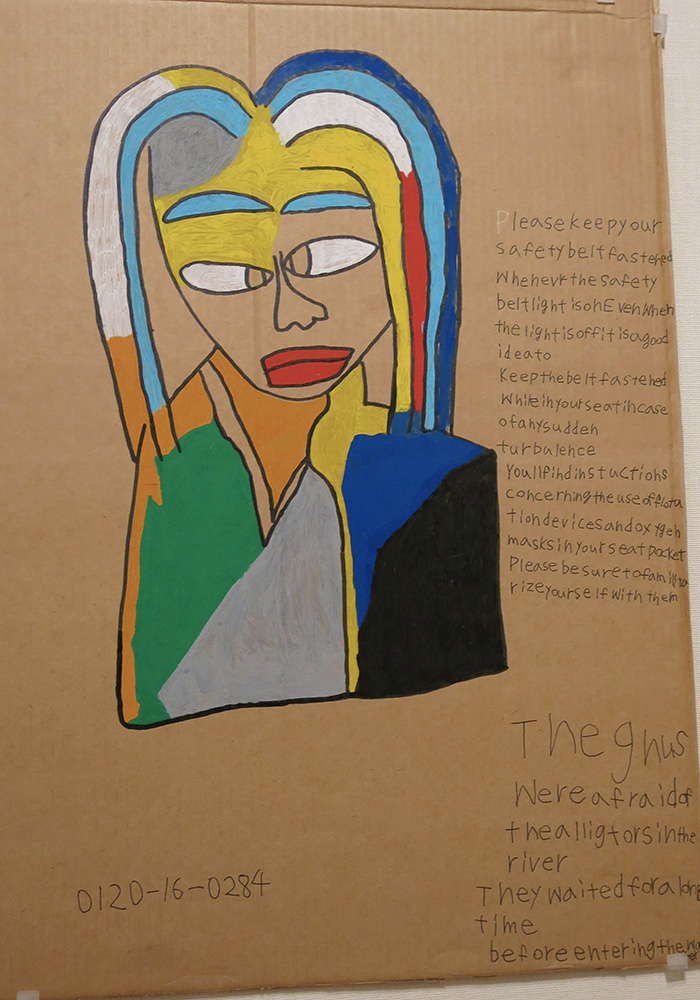

The late Masao Obata’s distinctive red crayon-on-cardboard works are made from boxes collected from the kitchen at his residential facility, which Obata stored in his room to draw on at night.

Takahiro Shimoda’s pyjama playsuits are emblazoned with his favourite foodstuffs. He simply wanted to wear the things he loves – hence salmon roe, fried chicken and pigeon-shaped cookies appear on his pajamas.

A section on ‘culture’ proves that, contrary to popular belief, these artists are keenly aware of their surroundings, of Japanese culture and international influences. Daisuke Kibushi’s postwar movie posters of classic films are created from memory, directly onto A3 sized copy paper with no preliminary drafts. Shoichi Koga’s handcrafted maquettes are inspired by traditional folklore and action fantasy films and Keisuke Ishino’s paper figurines allude to popular anime cartoon characters.

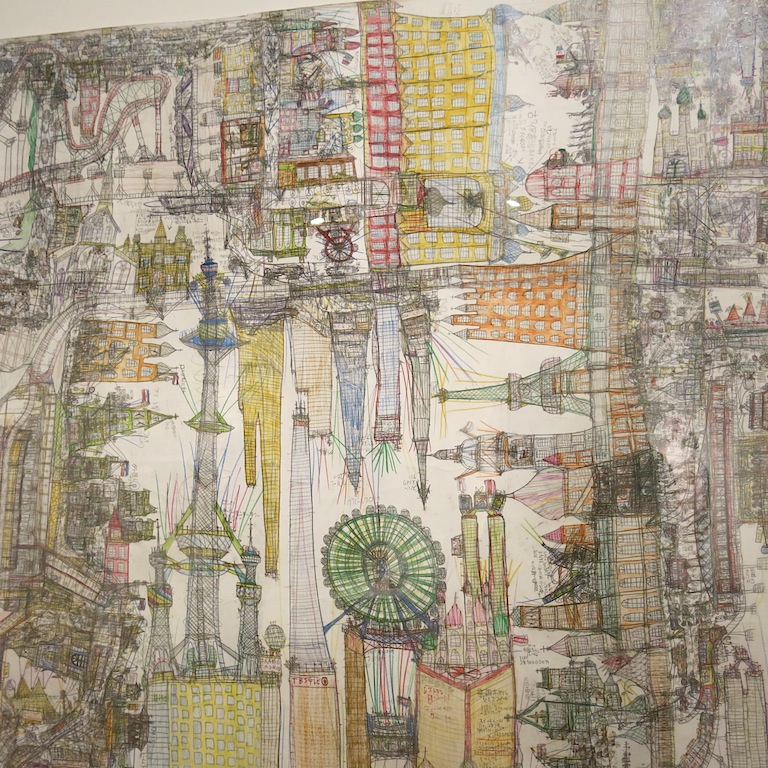

The final part of the exhibition is dedicated to ‘possibility’. This section focuses on inventiveness and features works which reorder information, “in a bid to understand or take control of the world around us.” Norimisu Kokubo’s fictional cityscapes explore real places that the artist has never visited, but learns about from newspapers and the Internet.

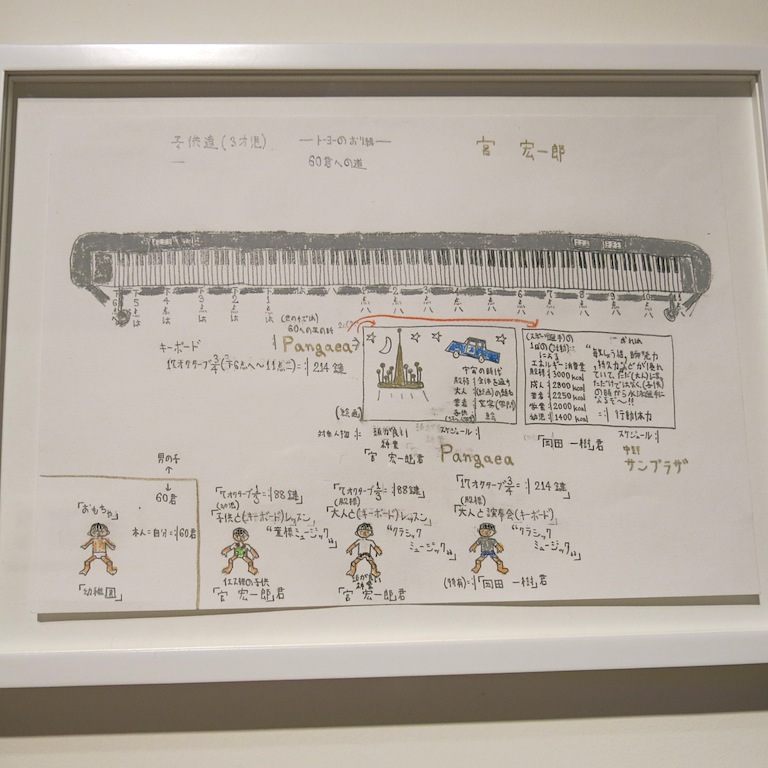

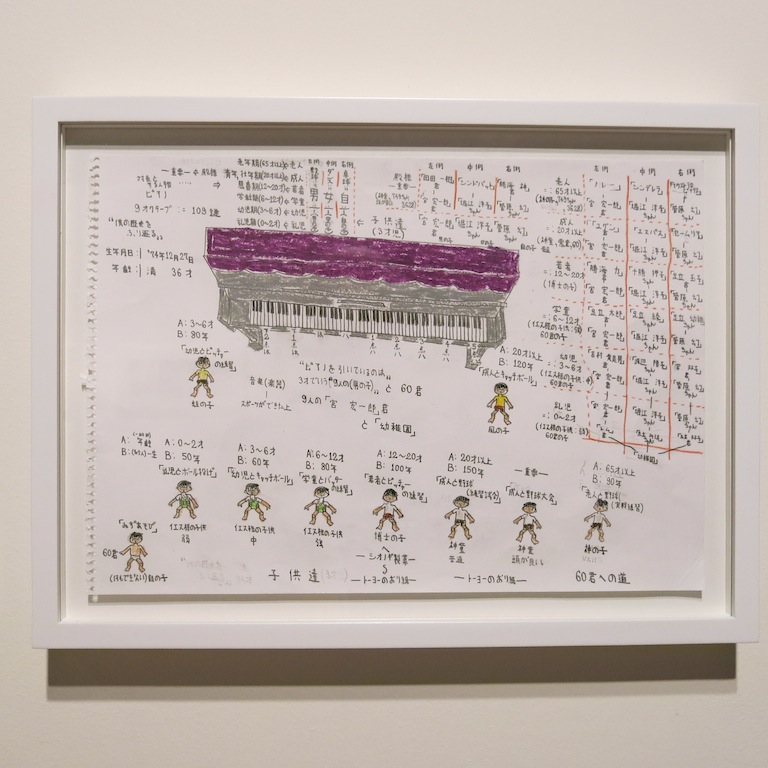

Koichiro Mia’s “statistic-strewn investigations into notions of ability, disability and super-ability’ are based on findings related to his calculations of the IQ and athletic ability of ‘normal’ people. He also uses piano keys to describe a human’s growth – normally the piano has 88 keys, but his have up to 214 keys… “this is a future,” he says. At school he played the organ and was fascinated with picture books about animals, space, science and biology.

Shinichi Sawada’s is autistic and barely speaks a word, but his spiked ceramic works depict a world populated by fantastical sea-monsters and mythical demons. Using his long, slender fingers with intricate precision, he works in silence and completes even his largest ceramic sculptures in 4-5 days.

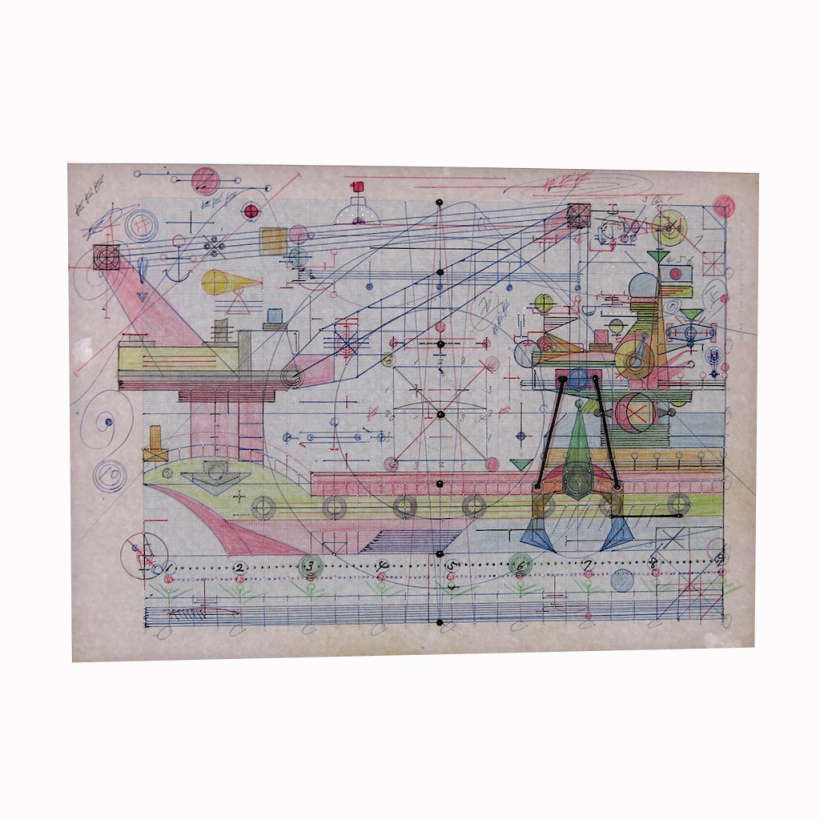

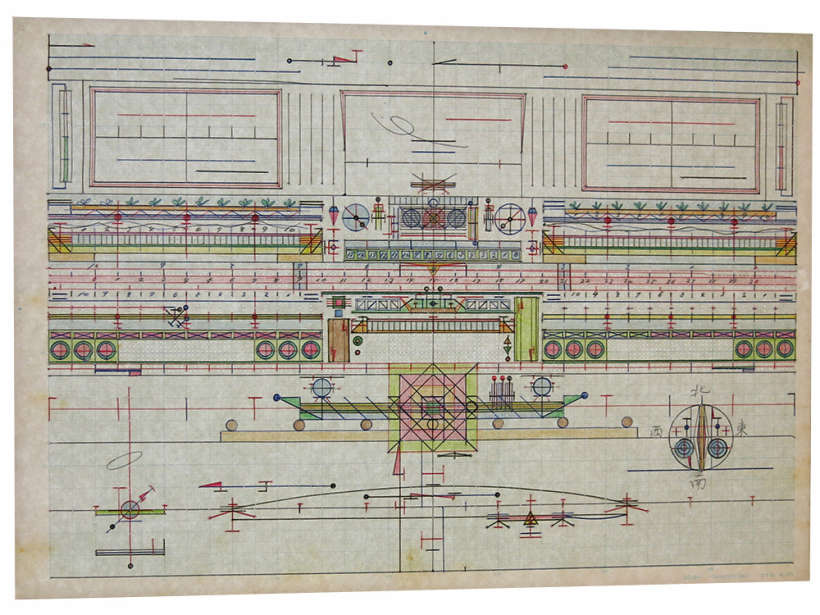

Kenichi Yamazaki creates carefully engineered blueprints using a compass, pen and graph paper. He developed a psychiatric illness whilst working as a construction worker in Tokyo. He has created nearly 3000 of his curiously engineered plans.

Documentary extracts featuring a selection of the artists at work can also be seen at the exhibition and are as moving as they are inspiring. If you are curious about life and art, this illuminating and heart-warming show is a must.

LEAVE A REPLY